Tender Tender

- Written by: Matthew Griffin |

- Created: Friday, 09 March 2012 17:28

"Tender1 requiring tact or careful handling"

"Tender2 To seek offers to carry out work, supply goods or buy land."– Oxford Dictionary

As the global urban development debate looks for new ways to deal with the economic crisis,

Berlin's recent history of ad-hoc development is gaining international recognition. Other

European cities are adopting Berlin's temporary use strategies, and building co-operative

(Baugruppen) models adapted to local conditions.

As the global urban development debate looks for new ways to deal with the economic crisis,

Berlin's recent history of ad-hoc development is gaining international recognition. Other

European cities are adopting Berlin's temporary use strategies, and building co-operative

(Baugruppen) models adapted to local conditions.

It is time to take these experiments to a new level. Ownership prestructures play a critical role in making innovative cities. Policy needs to be changed accordingly to support and encourage locally grown cities.

How land is entrusted, and to whom, constitute prestructures that have a massive effect on urban development. Once land is sold, cities have very little leverage to guide the long term processes that shape our built environment.

Accounting for the future

In Berlin, when public land is sold, it is sold to the highest bidder. The logic of this “maximize short term gain” is simple, and provided you have a functional and transparent marketplace, easy to evaluate. However urban economics are complex, and this simplistic approach may prove expensive. Over the Long term a community's needs may change, and the government may be forced to repurchace land it had previously sold.

Historic examples show that most such transactions have been far costlier to the community than the revenue generated by the sale. For an example, please see Control, my analysis of Berlin's GSW sale

A tender tender aims to address this issue by changing land sale processes to serve the community's long term interest, and at the same time involve as many citizens as possible in the property development. This article outlines five principles to guide this collaborative development process for public land, as an alternative to outright sales.

1. Maintain long term ownership

As cities sell their property, they are also divesting control. Once the land is sold, the owners have certain constitutional rights that make negotiating communal interests difficult or impossible. After a sale, the city has almost no influence on the quality of the urban environment, and it cannot steer the site's future uses to meet social needs.

By switching to a model based on leasehold,

the city can ensure that long term community interests will be met. Amsterdam, which owns eighty

percent of the property within the city, is run on leasehold principles. By mixing private

enterprise and public ownership, the city can precisely guide the development process,

maintain long term flexibility, and improve communal equity (in both senses of the word).

By switching to a model based on leasehold,

the city can ensure that long term community interests will be met. Amsterdam, which owns eighty

percent of the property within the city, is run on leasehold principles. By mixing private

enterprise and public ownership, the city can precisely guide the development process,

maintain long term flexibility, and improve communal equity (in both senses of the word).

Instead of selling a property, the city could lease it for a hundred years to local initiatives. This would guarantee long term stability for both the users and the city. It would also decouple the speculative value of the land from the functional value of the land, which in turn would help stabilize the cost of living and of doing business across the whole marketplace.

Because the city can maintain ownership of the land, it is also guaranteed income from the land in perpetuity, which would exceed the short term financial gains of a one time sale.

2. Preserve the future with stewardship

Because land is one of the city's inherently scarce resources, a tender tender process

needs to be based on sustainable values and goals.

Because land is one of the city's inherently scarce resources, a tender tender process

needs to be based on sustainable values and goals.

“Stewardship is an ethic that embodies responsible planning and management of resources....[it] is linked to the concept of sustainability...[and] a responsibility to take care of something belonging to someone else.”

When designing development processes, governments must act as stewards for future generations, not as short term crisis managers. Our cities have historic preservation departments. We propose integrating future preservation as an equally important component of urban development. This would ensure that spatial resources are accessible to future generations.

3. Find the best use, not the best price

In order to actively involve the community as collaborators in all phases of the development, a tender tender is structured around a managed dialogue with as many local participants as possible.

Public benefit can be measured in other ways besides a sales price. Often the way a site

is used (its program) generates more value for the community than the revenue from a sale.

Especially in difficult neighbourhoods, new programmatic strategies can address social

problems. The financial cost of these unsolved problems is often much higher than the

income generated by selling spatial resources.

Public benefit can be measured in other ways besides a sales price. Often the way a site

is used (its program) generates more value for the community than the revenue from a sale.

Especially in difficult neighbourhoods, new programmatic strategies can address social

problems. The financial cost of these unsolved problems is often much higher than the

income generated by selling spatial resources.

Finding the right use is a critical factor in any project's success. Failed investments are often caused by poor programatic decisions. When investments fail, the whole community pays the price; therefore it is only logical that the whole community be involved in the development process.

By running workshops instead of auctions, urban development projects can be integrated with local needs, visions and values. A development that is deeply intertwined with the neighbourhood will be more successful than one based on a top down decision.

4. Lower entry barriers to encourage collaboration

As technology reshapes society, collaboration is increasingly supplanting top down processes. This type of prestructural shift is as relevant to urban development as it is to software development. The collaborative paradigm behind open source software (Linux and Open Office) can also revolutionize the way we build and use our cities.

By lowering the barriers of entry, a tender tender aims to directly involve

broad layers of society in the development process.

By lowering the barriers of entry, a tender tender aims to directly involve

broad layers of society in the development process.

Currently public property sales processes are trimmed to the needs of medium and large scale professional and institutional investors. Bidding systems restrict active participation to a small circle of investors who have capital on hand, or backing from a financial institution. Re-structuring these processes to meet the needs of citizens and enabling small scale initiatives, would generate new waves of urban innovation to help transform our cities

During the workshop process the city could evaluate the proposed use of the site, and the initiatives involved in the project. It could then grant a two year option on a leasehold to the preferred bidder. This option would define the future contractual conditions, and give the initiative the time and security they need to organize financing, and finalize detailed planning. This rights allocation would also define contractual milestones and non-fulfillment consequences so the city can monitor progress.

By transforming land sales into a managed process of rights allocation, the whole system of urban development becomes more flexible. This lowers the barriers of entry. By involving citizens currently shut out of the development process, it vastly increases the economic potential of locally grown projects.

In Start-Up City we explored the value of entrepreneurship to the local economy. To integrate these innovative start-ups in the development process, the barriers of entry must be reformulated to accommodate their needs. With a tender tender the government could encourage flexible growth, from temporary to long term use. This would create more jobs, and a more stable local economy.

5. Harnessing private enterprise

Private enterprise is rightly seen as the most financially efficient way to organize

economic activity. The City of Amsterdam effectively couples private enterprise with

public ownership. Their model meets the city's long term needs and still generates

profitable opportunities for private enterprise.

Private enterprise is rightly seen as the most financially efficient way to organize

economic activity. The City of Amsterdam effectively couples private enterprise with

public ownership. Their model meets the city's long term needs and still generates

profitable opportunities for private enterprise.

By creating the right mixture of public and private initiative, the city can structure and guide urban development without taking on risks and responsibilities beyond its core competencies.

Berlin: evolving new strategies

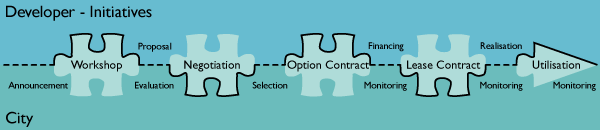

These principles outline the goals of a tender tender. Current land sale legislation needs to be updated to reflect the changing needs of our evolving society. Berlin is an ideal testing ground for these ideas. This diagram illustrates how it could work:

This article was published on May 5th 2012 in the Berliner Zeitung.