Locally Grown City

- Written by: Matthew Griffin |

- Created: Wednesday, 28 September 2011 17:56

Specificity as an Urban Catalyst

Globalization is grinding away the substance of our cities, transforming them into bad copies of each other.

Our Berlin based practice is exploring new strategies for small scale urban development to encourage more people to actively participate in creating the city.

We believe that it is the specifically local aspects which inspire people both to live in and to visit a city. Globally operating developers who build the same anonymous boxes everywhere are threatening the very life blood of our cities – their individual identity.

In an age where citizens strive to improve their environment by eating locally grown food, it is time to create Locally Grown Cities. This is no longer a tautology, but a radical statement against the hegemony of globalized business and cultural interests and a refreshing step towards improving our urban economy and the liveability of our cities.

D.I.Y. (and how it can all be different from what you think)

In this modern age of professionalization, the prestructures which define the creative possibilities of our profession have become a tight corset which is reducing the profession to that of facade decoration.

We see D.I.Y (Do It Yourself) as the alternative, the vanguard of experimentation because it gives architects the tools to expand their radius of action.

In our architecture practice we have experimented in many different fields. We started a gallery as a venue for our first experiments. Later we became software developers to encourage new approaches to urban planning. To build our first building we became real estate investors. Since then we have become activists to motivate Berlin politician's to implement new methods for urban development.

We innovate within our core profession by using these 'outside' roles to expand our field of influence. For instance as property developers we designed an economic model that allowed us to realize the architecture we envisioned. This meant we could let the architecture formulate the economics, rather than the other way around.

Develop the City — Develop Yourself

Until fairly recently, cities were primarily formed by individuals. The buildings they built reflected their personal values and goals because as it's owner, they were usually directly associated with the building.

Hence the city evolved in a local societal context that was directly expressed in the built environment.

Our context is Berlin. The most exciting projects in Berlin of the last decade have not been built by large corporate investors, but rather by individuals or small building groups that collectively construct their personal vision of living in this dynamic city. D.I.Y. is an immense challenge which expands your horizons on many different levels. The cost of our creative freedom, was substantial risk, measured out in sleepless nights.

As the foreman who poured the concrete for our first building said 'Building is life's last great adventure'.

If more people embarked on this adventure, our cities would be more inspiring, more dynamic, and more specific. It is time to recognize the value of this approach, and find ways to re-structure urban development policy to encourage locally grown cities.

What is a Locally Grown City?

A locally Grown City responds to the specific needs and visions of the people who live and work there, because it is created for and by them.

The locally grown city movement aims to return urban development into the hands of local, small scale actors.

Why would we want one?

Locally Grown Cities maximize grass roots innovation stemming from the creativity and skills of individuals. This can help cities to develop economically in difficult times, by strengthening the local economy, and reducing exposure to global volatility.

Locally Grown Cities create more specific places that are intertwined with the local fabric. They develop a bulwark against the globalization processes that force cities around the world to become more and more alike.

Where is this happening?

Locally Grown Cities often flourish in areas that have been shunned by global capital, or are suffering from economic distress.

Our personal experience has been drawn from Berlin development over the last two decades.

Who is doing it?

People working outside the conventional corporate structures. Most of the actors are primarily interested in goals other than financial return on investment.

Their radius of action intertwines property development with cultural entrepreneurship, business innovation, political activism, ecological realism, alternative medicine, and many other individual visions. This cross pollination adds cultural value to each building that cannot be measured by someone only interested in return on investment.

How to do it?

We seek to inspire others to move from the sidelines to participate in any way they feel empowered to. Active engagement with the city can compliment any walk of life; mix it in with education, cultural production, business or service.

A building cannot be separated from the life inside; the artificial schism that large investment structures create between activity and the shell in which it takes place must be mended. The unification of function and form in architecture would give our cities new flair, and intensify the urban mixture by extending the range of possibilities.

Our Own Experiments

Our office has been experimenting with strategies for executing and encouraging Locally Grown Cities. From theoretical experiments, to full blown development work, we have explored various avenues.

Urban Issue (1997 — 1999)

In 1997 we founded a group gallery that was an experimental space focused on cities.

The space was based on 'coincidence without consensus';eeach member could organize the events and exhibitions of the Urban Issues that interested them.

Deadline created a spectacular light installation for the opening night on November 14 1997.

The gallery was a space that acted like a city, inviting and involving people to create activity, within an open structure. The people defined the place through their actions. This identity, or place, influenced a whole generation of young Berlin architects. It was a meeting ground, and a space to experiment

StadtBilding (1998)

One of our experiments in the Urban Issue space was Stadtbilding. We created a 'city'in the gallery together with all the visitors to the exhibition.

There were no rules governing its construction, the goal was to build a city without resorting to hierarchical authority.

During the exhibition, the 'city' expanded over the pixelated walls of the gallery,each pixel being one A4 sheet of paper. Visitors made the city grow, by performing one of three jobs: delivering material for the city (scanning images or objects), planning the city (modifying the huge image file in the computer), or constructing it (placing freshly printed pixels on the wall).

People reacted to the existing context differently. Some were concerned with how their intervention developed the city as a whole, and some just did their thing. The construction activity became a social event in itself, to the extent that one visitor spontaneously celebrated his birthday party there.

Templace.com (1999 — 2003)

Templace.com is a web system we created as the cornerstone of the Urban Catalysts research project. It aimed to establish temporary use as an alternative to traditional city planning and development by providing temporary users, landlords, municipalities, and planners with online communication and management tools and information resources for practical support and theoretical inspiration.

It was a direct attempt to use the advances in technology to change the way we use cities by empowering more people to participate directly in urban processes.

SlenderBender (1999 — 2004)

To build SlenderBender we stepped beyond the role of architects to become developers.

By bundling client and architect, we could focus the project more precisely and consistently than would have been possible in a conventional client architect relationship. This meant we were able to avoid the common problem of good architecture being sacrificed to a client's financial agenda. Although we could not ignore the financial and legal limitations placed upon us, we refused to let them dominate in decisions that would undermine our goal of creating an outstanding building.

One building is a very small step towards creating a locally grown city. We hope that our example inspires others to do the same, in a small wave of change.

In the ensuing years in Berlin, many more architects have taken this step towards regaining creative control of their work. The results are encouraging, and they have added a new dimension to the local cityscape.

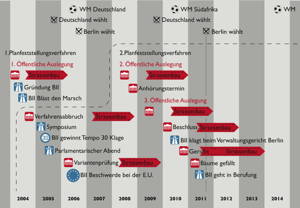

Bürgerinitiative Invalidenstrasse (2004 — 201?)

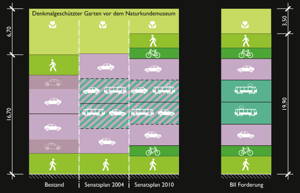

People experience cities from the street. Whether walking, biking, driving, or riding a tram, the design of a street has a huge impact on our daily lives. Why aren't architects involved in street design?

In 2004 when the Berlin Senate began formal proceedings to transform the Invalidenstrasse from a two lane to a four lane street, we began to realize that Berlin was not the progressive city it proclaimed itself to be.

To make room for four lanes they planned to eliminate one footpath, devastate a historically listed garden, and force the new tram line to share its lane with the cars. No provisions were made for a bike lane. The plan intended to triple traffic to 40.000 cars per day, without any concessions to the other modes of transportation that make up 69% of Berlin's modal split.

Because the Invalidenstrasse runs parallel to our home, and I walked it almost every day, I could not bear to see it sacrificed in the name of automotive efficiency.

Their plan could have been taken straight out of a 1970's traffic planning handbook. It had absolutely no regard for the tender balance between the many participants in this street, which is blessed with three important museums, and many university and government buildings.

Together with a handful of other neighbours, we founded an initiative to fight for a more sustainable plan. We worked constructively with local politicians and preservationist groups to propose a more balanced solution. Our main demands were separate lanes for bikes, for pedestrians, for cars and for the tram.

Working with volunteer traffic planners we devised a solution which could deliver as much car throughput as Berlin's plan without destroying the urban fabric.

Unfortunately Berlin's Urban Planning Senator, Ingeborg Junge-Reiher refused to negotiate with us, and pursued a hard nosed legal battle. Although we have been successful in achieving a bike lane, preserving one foot path, and saving several trees that would have otherwise been cut down, the city still insists that the trams share their lane with the cars.

Even though we are still challenging the plan in the courts, the city began construction in May 2011, six years later than they originally planned.

Team Eleven

“Wir reden über Grund und Boden weil wir darum gämpft haben” -- Britta Jürgens.

“Wir reden über Grund und Boden weil wir darum gämpft haben” -- Britta Jürgens.

(We discuss property because we he had to fight for it)

As part of a group of engaged young Berlin architects we have become politically active to find new strategies to resolve Berlin's looming housing shortage.

Berlin has ignored the problem of low income housing ever since its last programs to fund social housing ended in 1997. In 2003 it resolved to nullify all funding to private contracts for existing social housing not owned by the city.

We are currently working constructively with local politicians towards testing new approaches.

Locally Grown City

We see our practice as a multifaceted field of action that revolves around the city. Our own 'doing' is a testing ground for new ways to influence the urban and social structure that makes our cities tick.

By inspiring others around us to become involved, we hope that cities will start becoming more local, meaningful places.

Based on a lecture given by Matthew Griffin at The Technical University in Vienna on 20.05.2011